Want to take a deep dive into the friendship between Wyatt Earp and Doc Holliday? We've compiled a list of some of the best books and movies about the pair.

by Gary L. Roberts 8/11/2017 4/27/2024

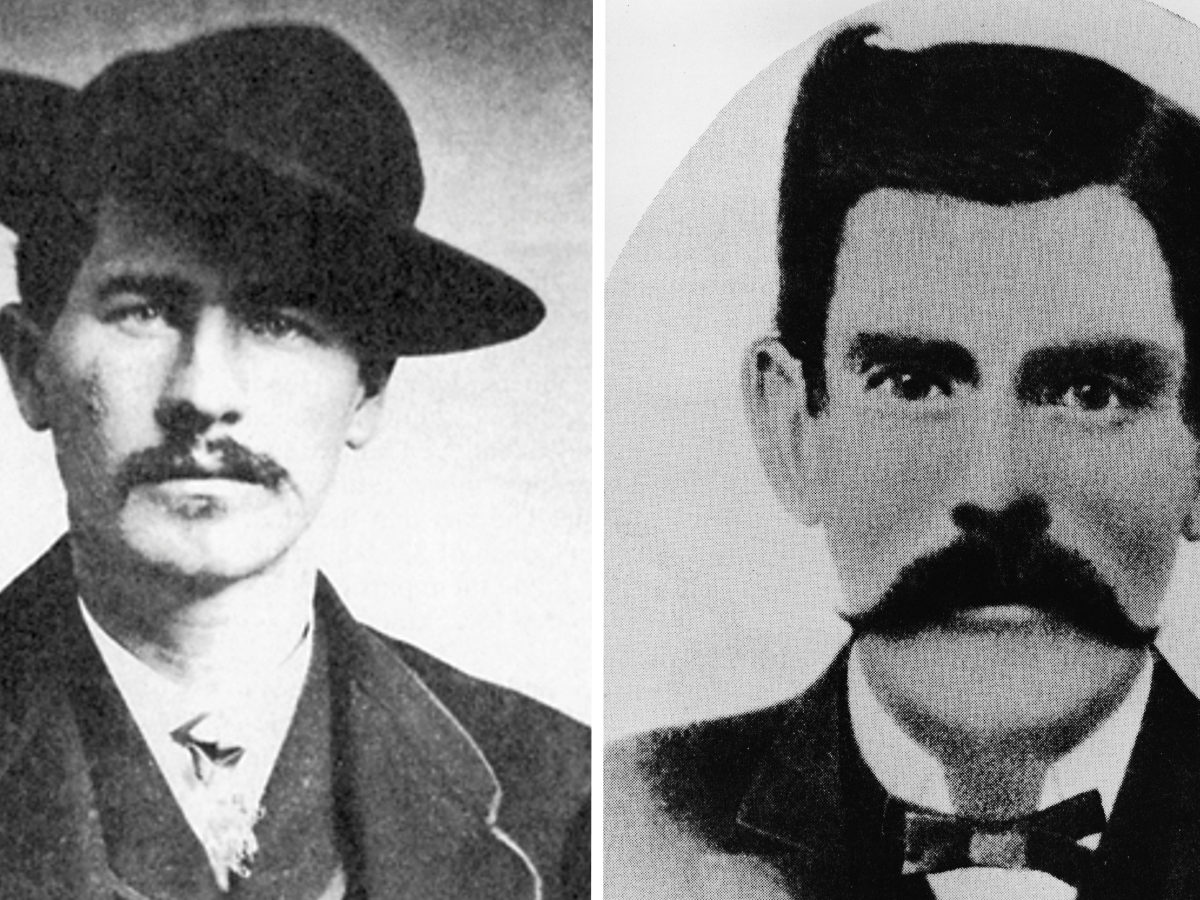

Wyatt Earp and Doc Holliday, two of the American West’s most legendary figures, were unlikely friends (or were they?). Despite their differences in personality and backgrounds — one, a lawman; the other, a gunfighter — they remained loyal friends for much of their lives. After the Gunfight at the O.K. Corral, their legend grew — along with an insatiable interest in their outsized personalities and tales of their adventures across the West.

Want to take a deep dive into the long friendship between Earp and Holliday? Aside from HistoryNet’s deep resources on the legendary duo, we’ve compiled a list of some of the best books and movies about the pair.

(1927, by Walter Noble Burns, republished in 1999 with foreword by Casey Tefertiller)

This is the first book to give any real form to the life of John Henry “Doc” Holliday, whom Burns portrayed as a delicate-appearing Southern gentleman, but a man with no scruples save convenience and courage. It’s a compelling and influential portrait, even if the information Burns presented is incomplete, and he was mistaken on some key points. As for Wyatt Earp, Burns did not glorify him or apologize for him but explained him as a man who had no regrets. Burns’ view of the Wyatt-Doc friendship has a 19th-century edge to it, most likely reflecting his own values: “So these two friends stood side by side through good and evil report, through fortune and misfortune, through thick and thin, and back to back they fought in the swirling gloom of the final storm that threatened to engulf them.”

(1931, by Stuart N. Lake)

In a book well received when first published, Lake portrayed Wyatt Earp as a hero—a portrayal that dominated the field for decades. Lake was plainly uncomfortable with Doc Holliday and his role in Earp’s life. Holliday was incompatible with the Earp he presented. How could a man as good as Earp be friends with a man as bad as Holliday? He concluded that Doc’s friendship for Wyatt was “of considerable significance” to any study of Earp and that “an accurate appraisal of Holliday” is essential to understanding Earp’s life. In Lake’s hands Doc comes across as a caustic, consumptive, nervy, deadly gunfighter devoted to Wyatt, while Wyatt’s friendship for him is justified in terms of Earp’s integrity, gratitude and loyalty to a man he thought was blamed for things he did not do. “Mind me,” Lake has Earp say, “Doc Holliday was no saint, and no one knows that better than I. But even the Devil is entitled to his due, and for reasons which will appear, I’d like to see Doc Holliday get his.” This accentuates Wyatt’s goodness, not Doc’s badness.

(1955, by John Myers Myers, republished in 1973; and 1957, by Pat Jahns, republished in 1979)

These two 1950s books are presented together here because each in its own way, though dated, offers particular insights and different perspectives on the friendship of Holliday and Earp. They represent the transition in the view of Wyatt Earp from the heroic image of Stuart Lake to the more critical view of the“debunkers” who dominated the 1960s. Myers filled in many of the gaps in Doc’s life. He believed Wyatt did not learn of Doc’s passing until 1895. “Doc and Wyatt had no more inclination to correspond with each other than do the average footloose males.” He believed Earp’s 1896 article was in part a tribute to Holliday. Jahns’ view of Doc was very different. She portrayed him as pleasant, in love with his first cousin, Mattie Holliday, embittered by his tuberculosis, and addicted to gambling and alcohol. Doc was drawn to Earp “as the very embodiment of the silent, manly personality.” She believed “neither one of them did the other any good,” but “the time came when Doc and Wyatt were always seen together, inseparable friends.” She saw Doc as weak, dependent and a terrible shot, and Wyatt as a self-absorbed, insecure exhibitionist. She wrote: “Two more completely misunderstood men never lived than Doc Holliday and Wyatt Earp. They probably never understood each other until one day in Pueblo, Colorado, in the late spring of 1882. And then they never spoke to each other again.”

(1997, by Casey Tefertiller)

The friendship of Holliday and Earp puzzles Tefertiller. “The unusual friendship between Earp and Holliday can never be fully understood,” he writes. For him a key factor in the relation was Earp’s acceptance of Holliday as a man, without regard for his shortcomings or his disease. He presents Holliday as consistently loyal and appreciative of Earp’s acceptance. Wyatt became a real person with this book, not just a two-dimensional figure representing either good or evil. Tefertiller does not belabor the point of their friendship. He does detail the benefits and costs to Earp. He notes the quarrel in Albuquerque that led to their parting “was minor enough not to have impaired their friendship.”