The European Union (EU) faces many health-related challenges. Burden of diseases information and the resulting trends over time are essential for health planning. This paper reports estimates of disease burden in the EU and individual 27 EU countries in 2019, and compares them with those in 2010.

We used the Global Burden of Disease 2019 study estimates and 95% uncertainty intervals for the whole EU and each country to evaluate age-standardised death, years of life lost (YLLs), years lived with disability (YLDs) and disability-adjusted life years (DALYs) rates for Level 2 causes, as well as life expectancy and healthy life expectancy (HALE).

In 2019, the age-standardised death and DALY rates in the EU were 465.8 deaths and 20,251.0 DALYs per 100,000 inhabitants, respectively. Between 2010 and 2019, there were significant decreases in age-standardised death and YLL rates across EU countries. However, YLD rates remained mainly unchanged. The largest decreases in age-standardised DALY rates were observed for “HIV/AIDS and sexually transmitted diseases” and “transport injuries” (each -19%). “Diabetes and kidney diseases” showed a significant increase for age-standardised DALY rates across the EU (3.5%). In addition, “mental disorders” showed an increasing age-standardised YLL rate (14.5%).

There was a clear trend towards improvement in the overall health status of the EU but with differences between countries. EU health policymakers need to address the burden of diseases, paying specific attention to causes such as mental disorders. There are many opportunities for mutual learning among otherwise similar countries with different patterns of disease.

• This article, systematically analysing GBD 2019 study estimates, presents an overview of the state of health in the European Union in 2019, compared to 2010.

• There was an improvement in the overall health status of the EU, despite substantial differences between Member States.

• Cardiovascular diseases and neoplasms are the major contributors to the overall burden of diseases in the EU in 2019.

• The age-standardised rate of years lived with disability due to mental disorders has been increasing and is expected to increase even more because of the COVID-19 pandemic.

• This report provides a framework upon which to base further region- and country-specific health policies and interventions, to support health planning and priority setting.

The European Union (EU) faces many challenges that impact current and future population health, including complex issues such as population ageing, digital and green transitions, socio-economic challenges and the organisation of health systems. In addition, there are still significant differences in health status between EU countries which are associated with factors such as structural and budgetary differences, variations in the effectiveness of public health policies and health related risk factors [1,2,3,4,5,6]. In fact, health systems differ across the EU and, for instance, while the 2008 global financial crisis reduced annual health budgets, this did not happen uniformly. In addition, as population ageing advances, multimorbidity and frailty are becoming more common and need to be addressed to improve the well-being of EU countries [7,8,9].

According to Eurostat, life expectancy at birth in the EU was 81.0 years in 2019, with women living, on average, 5.5 years longer than men [4, 10]. Beyond life expectancy, population health can be summarised through combined health metrics such as health-adjusted life expectancy (HALE) and disability-adjusted life years (DALYs). DALYs consist of two components: (i) years of life lost (YLLs), which captures health loss due to premature mortality, and (ii) years lived with disability (YLDs), which quantifies health loss due to morbidity. A previous study showed a decline in YLD and DALY rates, an increase in life expectancy of 5.9 years and an increase in HALE of 4.6 years, on average, from 1990 to 2017 among EU-28 countries [11]. However, another study concluded that, despite the improvement in the health status of the EU, several central and eastern European countries had not experienced such pronounced gains in overall health in comparison to the EU-15 [12].

Accurate and timely data on mortality and morbidity, caused by diseases and injuries and their trends over time are essential to assess the impact of health strategies and assist policy makers in improving health planning and priority setting. This information can also be used to understand between-region variations, providing opportunities for mutual learning among EU countries. The Global Burden of Disease (GBD) study generates estimates of population health using a wide range of metrics, capturing the impact of diseases, injuries and risk factors on health. Furthermore, it allows for comprehensive comparisons over time and across countries. Burden of disease estimates are increasingly used in the EU and globally, as they provide a comprehensive and comparable picture of the overall population health status. An earlier analysis of the results from the GBD 2017 study for the EU countries examined changes since 2007 for the burden of diseases and injuries in the EU-28 in 2017 [13]. Between the release of the GBD 2017 and the GBD 2019 datasets, several improvements were made, including key demographic modelling steps, preferred/reference case definitions or measurement methods and the development of a Bayesian meta-regression tool, as well as the inclusion of more data sources and 12 new causes [14, 15].

In this paper, we analyse the GBD 2019 study estimates (focusing on deaths, YLDs, YLLs, DALYs, life expectancy and HALE) and compare the years 2019 and 2010 to describe the current health status of the EU. The aim of this study is to provide a picture of the state of health in the EU-27 countries in 2019, to examine how these have changed since 2010 and to highlight meaningful opportunities that exist to improve health across the continent.

We obtained estimates from the 2019 GBD study for the EU-27 region and for the 27 EU countries individually. Considering the period of analysis, the 27 EU member states countries included were: Austria, Belgium, Bulgaria, Croatia, Cyprus, Czech Republic, Denmark, Estonia, Finland, France, Germany, Greece, Hungary, Ireland, Italy, Latvia, Lithuania, Luxembourg, Malta, Netherlands, Poland, Portugal, Romania, Slovakia, Slovenia, Spain and Sweden.

A detailed description of methods and results used in GBD 2019 has been published elsewhere [14,15,16,17]. In brief, the GBD 2019 study is a collaborative effort of more than 5,000 researchers, aiming to measure population health at global, regional and national levels by quantifying the burden of 369 diseases and injuries (i.e. 286 causes of death and 364 non-fatal causes) and 87 risk factors between 1990 and 2019 for 204 countries and territories. Several improvements were made in the GBD 2019 study, including key demographic modelling steps, reference case definitions or measurement methods and the Bayesian meta-regression tool. In addition, more data sources and 12 new causes were added to the GBD modelling framework, including pulmonary arterial hypertension, nine new sites of cancer, and two new sites of osteoarthritis (hand and other joints). The GBD produces estimates of incidence, prevalence, mortality, YLDs, YLLs, DALYs, life expectancy and HALE for the entire time span between 1990 and 2019. Cause-specific death rates and cause fractions are calculated using the Cause of Death Ensemble model (CODEm) and spatiotemporal Gaussian process regression. They are adjusted to match the total all-cause deaths calculated as part of the GBD population, fertility, and mortality estimates [15, 18].

DALYs consist of two main components: YLLs and YLDs. YLLs are calculated by multiplying the number of deaths of each age the remaining life expectancy (RLE) at age of death derived from the GBD standard life Table [19]. YLDs are estimated by multiplying the prevalence counts by the disability weight for each specific health outcome associated with a given disease or injury, with further adjustment for co-morbidity and severity. A Bayesian meta-regression modelling tool, DisMod-MR (Disease Modelling-Meta Regression) 2.1, ensures consistency between all epidemiologic metrics for most causes [16]. HALE accounts for years of life spent in good health and serves as a summary for both mortality and morbidity [13]. It thus corresponds to specific LE by age and geography, adjusted for the years spent living with disability and disability weights. All estimates are reported with their 95% uncertainty intervals (UI). UIs are propagated throughout the estimating process where 1000 draws are generated for each point estimate, and the 95% UIs are obtained by selecting the 2.5th and 97.5th percentiles of the draws. This approach ensures robustness in identifying meaningful differences and trends in health outcomes over time.

The statistical significance of the difference between two estimates was defined as the absence of overlap between the 95% UI of those estimates. We analysed the overall (all ages and both sexes) and age group-specific rates for men and women. To analyse trends between 2010 and 2019, we relied on age-standardised rates and their relative changes since 2010. Difference between 2010 and 2019 was expressed in percentage change since 2010 (i.e. \(_=\frac_-_>_>\times 100\) ). In the GBD 2019 study, the same methodology is applied across years, including for 2010 and 2019. Age-standardisation is based on the GBD 2019 world standard population, which adjusts for differences in age distributions across populations, ensuring comparability between groups with different age structures. These rates were calculated using methodologies outlined in the GBD study, which provides upper and lower bounds of the estimates, allowing for a comprehensive analysis of trends over time.

The GBD arranges diseases and injuries (causes) into hierarchically nested categories in four levels of aggregation. At every level of aggregation, causes are mutually exclusive and collectively exhaustive. We extended this analysis focusing on each of the 22 Level 2 causes, and including seven Level 2 causes from Level 1 in the “communicable, maternal, neonatal and nutritional diseases” group (enteric infections, respiratory infections and tuberculosis, HIV/AIDs and sexually transmitted infections, maternal and neonatal disorders, neglected tropical diseases and malaria, nutritional deficiencies, other infectious diseases), 12 in the “non-communicable diseases” (NCDs) group (cardiovascular diseases, chronic respiratory diseases, diabetes and kidney diseases, digestive diseases, mental disorders, musculoskeletal disorders, neoplasm, neurological disorders, sense organ diseases, skin and subcutaneous diseases, substance use disorders, other NCDs), and three in the “injuries” group (self-harm and interpersonal, unintentional injuries and transport injuries). We considered Level 2 causes to focus the analysis on broad disease categories due to their policy implications. These causes represent broad disease categories where policy implications can result in benefits for all conditions summarized in these broader categories. We thus provide insights into the major drivers of health outcomes within the population.

All results are based on the estimates extracted from the Global Burden of Disease Results database and GBD Compare [20, 21]. All analyses were carried out with the open-source R Statistical Software (version 3.4, Foundation for Statistical Computing, Vienna, Austria) [22]. The GBD study adheres to the Guidelines for Accurate and Transparent Health Estimates Reporting (GATHER) standards developed by WHO and others [23].

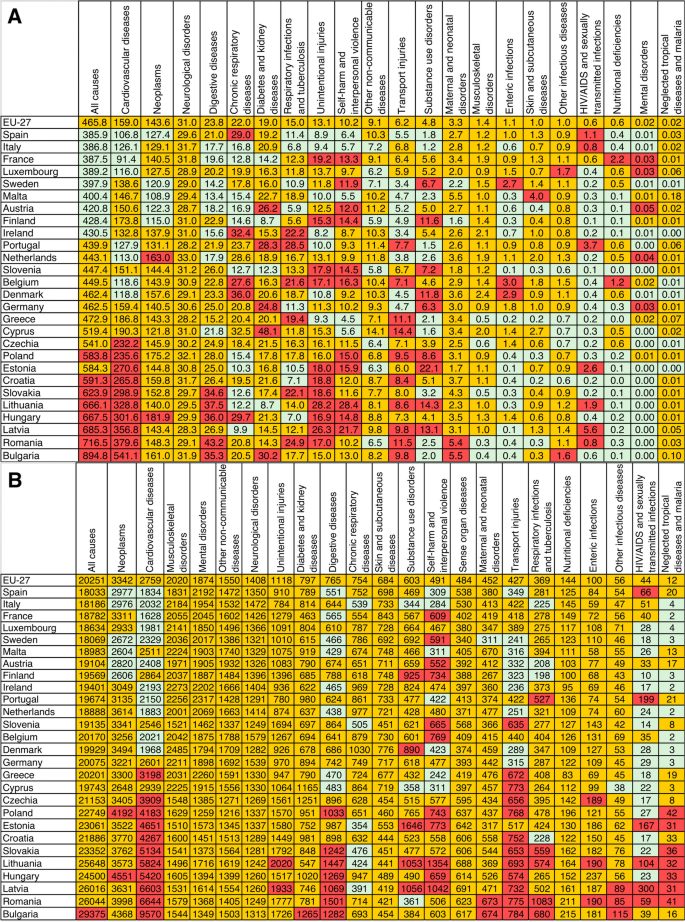

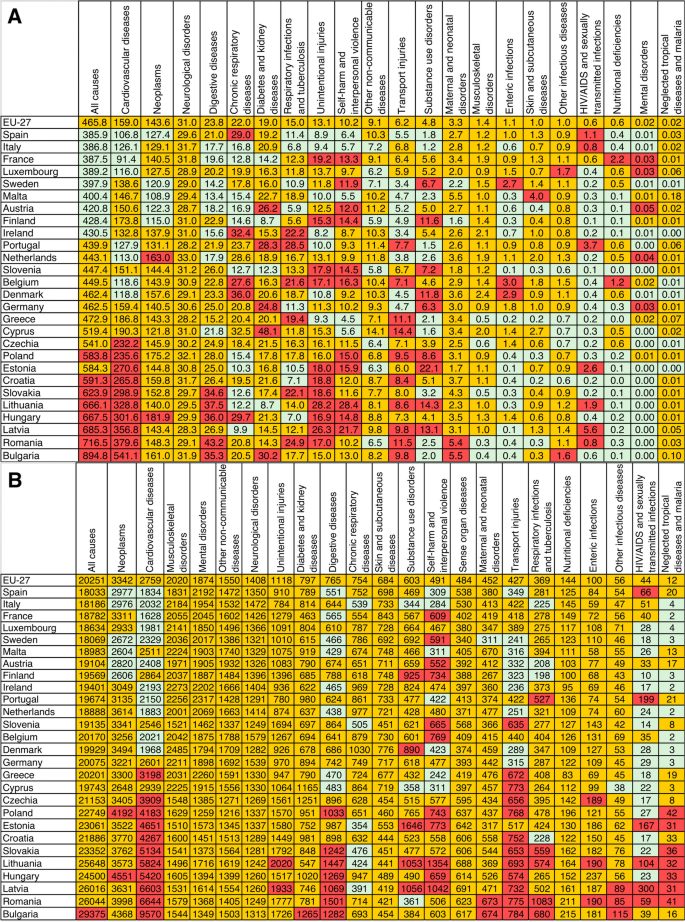

In 2019, the EU-27 had a total of 5,354,279 (95% UI: 5,206,626; 5,502,691) all-cause deaths, yielding a crude death rate of 1040.3 (95% UI: 1011.6; 1069.1) per 100 000 inhabitants. The age-standardised death rate for all causes was 465.8 (95% UI: 451.2; 480.9) per 100,000 inhabitants in the EU, with high variability across countries, ranging from 894.8 per 100,000 in Bulgaria to 385.9 per 100,000 in Spain. The total number of all-cause DALYs was 157,884,271 (95% UI: 139,041,970; 178,511,173), with a crude rate of 30,675 (95% UI: 27,014; 34,683) per 100,000 inhabitants. The all-cause age-standardised DALY rate per 100 000 inhabitants in 2019 was 20 251.0 (95% UI: 17 408.1; 23 513.9).

Eight countries (Bulgaria, Romania, Latvia, Hungary, Lithuania, Slovakia, Croatia, and Poland) reported significantly higher (i.e., the lower limit of the individual country 95% UI was higher than the upper limit of the EU 95% UI) all-cause age-standardised death rates than the EU. In contrast, nine countries (Spain, Italy, France, Luxembourg, Sweden, Malta, Austria, Finland, and Ireland) had significantly lower rates than the EU (Fig. 1A; Table 1). The all-cause age-standardised death rate in the EU declined on average by 8.8% (95% UI: -11.7; -5.9), ranging from -4.8% (95% UI: -7.2; -2.3) in Greece to -18.5% (95% UI; -30.7%; -4.5%) in Lithuania.

In 2019, the age-standardised death rates for cardiovascular diseases were significantly higher than the EU rate (159.0; 95% UI 142.2; 169.2) in most Central and Eastern European countries, with the highest values in Bulgaria, Romania, and Latvia, and significantly lower than the EU rate in some Western European countries (Fig. 1A). A similar geographic pattern was observed for age-standardised DALY rates for cardiovascular diseases, the second leading cause of age-standardised DALY in the EU (Fig. 1B).

Compared to the EU, the age-standardized death (143.6; 95% UI 133.8; 150.1) and DALY (3,342; 95% UI 3,175; 3,505) rates for neoplasms in 2019 were significantly lower in Spain, Sweden, Malta, Austria, and Finland (Fig. 1A and B). Hungary and Netherlands showed a significantly higher age-standardised death rate, with Hungary and Poland having a significantly higher age-standardized DALY rate (Fig. 1A and B). In fact, the age-standardised death rate in Hungary was almost two times higher than in France. Neoplasms were the leading cause of age-standardized DALY and the second highest cause of age-standardised mortality across the EU in 2019.

Digestive diseases are another example of high variability in death rates in EU countries. The highest (in Romania) to the lowest (in Malta) age-standardised death rates ratio is over 3.2. Additionally, countries of Central and Eastern Europe (Romania, Lithuania, Bulgaria, Hungary, Slovakia, Latvia, Poland) had significantly higher DALY rates than the EU rate.

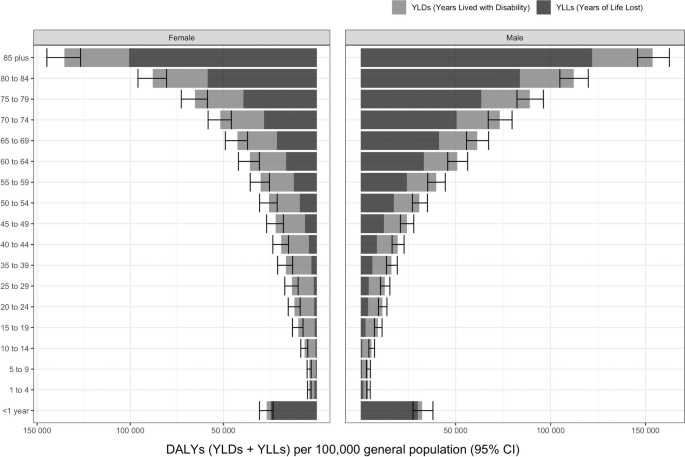

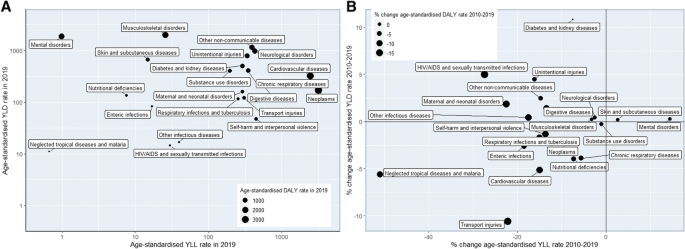

Figure 1A and B show the age-standardised death and DALY rates, respectively, for the EU and each EU country in 2019, for all Level 2 causes, comparing each country with the EU. Causes had different patterns across EU countries. For example, for HIV/AIDS and sexually transmitted infections, Latvia and Portugal had the highest age-standardised death and DALY rates, with more than five times the EU. The contribution of fatal and non-fatal components of age-standardised DALY rates varied substantially across Level 2 causes (Fig. 3A). For neoplasms and cardiovascular diseases, YLLs contributed more than YLDs, while for musculoskeletal and mental disorders, the total DALYs were almost exclusively YLDs.

Figure 3B highlights the relative change in age-standardised YLL, YLD and DALY rates between 2010 and 2019 for Level 2 causes. Age-standardised YLL rates declined for all causes except for mental disorders (14.5% increase) and skin and subcutaneous diseases (2.6% increase), while Level 2 causes were quite evenly split between increases and decreases for age-standardised YLD rates. The largest decreases in age-standardised DALY rates were observed for HIV/AIDS and sexually transmitted diseases (-19.2%) and transport injuries (-19.1%). On the other hand, only diabetes and kidney diseases showed a significant increase (3.5%) for age-standardised DALY rates in the EU between 2010 and 2019, mainly due to the age-standardised YLD rate increase. Finally, it is worth mentioning that mental disorders showed a non-significant increase for age-standardised DALY rates between 2010 and 2019 and this increase was mainly due to YLL rates, although there was also an increase in age-standardised YLD rates.

This study presents an overview of the state of health of the EU-27 and individual Member States in 2019, comparing the findings with data from 2010 to examine changes over the last decade. The results indicate that most countries experienced a significant, albeit varied, reduction in all-cause, age-standardised mortality and YLL rates over this period, although this pattern differed by country and region. During this time period, there were no substantial changes in all-cause age-standardised YLD rates, with the increase in the Netherlands being the most notable. The EU all-cause, age-standardised DALY rate fell by 5.8% over this period, mirroring global trends [15].

The observed variability in all-cause age-standardized death rates across countries in 2019 indicates that there are geographical clusters of mortality in the EU. The pattern of mortality burden clusters with a clear geographical variation across the EU was also observed for life expectancy rates and HALE measures. This pattern has been previously highlighted [13]. However, despite recent progress to reduce these differences, its persistence suggests that improvements may not continue uniformly across the EU without enhanced, combined and coordinated efforts to address a wide range of inequalities across health determinants, including socioeconomic factors.

Neoplasms and cardiovascular diseases were the leading causes for the burden of disease in the EU in 2019; both are attributable to the behavioural risk factors and depend on early diagnosis, treatment and management of risk factors. Inherently, these are among the costliest diseases for EU countries [24]. Additionally, with population ageing, NCDs are expected to increase over time and represent a greater proportion of overall deaths with higher mortality rates associated with cancer and cardiovascular disease relative to communicable diseases [25]. A recent analysis of changes in mortality and disability, comparing data from the GBD 1990–2019, confirmed this trend, finding that there has been an overall increase in disease burden among older Europeans during this time period, primarily driven by cardiovascular diseases [26]. These changes have not been homogeneous across the EU. As structures and systems take time to adapt to such changes, it suggests that existing differences may magnify if intervention strategies are not urgently introduced. Examining age-standardised DALY due to cancer, rates in the EU were between those of China (higher rate) and the United States of America (lower rate) [27]. EU countries had an estimated cancer burden of 4 million new cases annually in 2020, with cancer disproportionately affecting older Europeans and those living in Eastern EU Member States [28]. Future interventions must be designed to address the main drivers of NCDs, including population ageing, changes in population structure, and improvements in population-level risk factors, also considered in the Europe's Beating Cancer Plan. These must also address reasons for important differences across European regions. For example, despite the existence of cancer screening programmes across EU countries, differences in uptake of cancer screening varies according to socioeconomic factors; inequalities including lower household income, higher unemployment, and lower levels of educational attainment are associated with reduced uptake, especially in Eastern EU member states [29]. A similar trend is seen for cardiovascular diseases. EU member states with lower income levels and greater degrees of socioeconomic inequalities have disproportionately higher incidence rates and a greater burden of cardiovascular disease [30].

In this study, age-standardised death rates between countries varied widely by disease. For example, the results draw attention to the preventable high rates of self-harm and interpersonal violence across the EU in 2019. These mainly affected younger age groups. Although rates vary across the EU, we observed a geographical pattern with higher rates in the Baltic region. These differences in self-harm have been shown previously and likely relate to differences in the burden of mental disorders across the EU [31]. Baltic countries have historically had the highest rates of alcohol-related mortality and suicide, as well as a high burden of mental and behavioural disorders [32].

Infectious diseases, in general, represented a small share of age-standardised death rates until 2019, presenting an optimistic scenario regarding these most preventable diseases. There was, however, considerable heterogeneity in age-standardised death rates for some infectious diseases such as HIV and sexually transmitted infections, which despite overall low rates, had prominent outliers with relatively high rates in Latvia and Portugal. This highlights the importance of national preventive programmes that tackle the different transmission pathways, alongside with strengthening of surveillance systems [33].

Besides this heterogeneity, such infectious diseases showed an increased age-standardised YLL rate. This will be difficult to overcome without tailored health policies as the incidence of HIV is still increasing in several EU countries [34]. Moreover, infectious diseases are likely to represent a growing share of total disease burden following the COVID-19 pandemic, and will likely be of great importance in future GBD revisions.

Regarding DALYs, remarkable regional differences were found in cardiovascular diseases, self-harm and transport injuries, which were significantly higher in Eastern EU countries. Mental disorders were the fourth highest cause of age-standardised DALY rates and did not show a decrease over recent years. In fact, they showed a non-significant increase, mainly due to a remarkable increase in YLL. These conditions also represent one of the leading causes of YLD, which has been rising over recent years and has increased even more following the COVID-19 pandemic [35, 36]. Additionally, self-harm and interpersonal violence may also be linked to mental disorders, as an example of interacting causes. Thus, viewed as a whole, mental health disorders and other related possible outcomes such as self-harm and mortality linked to mental disorders, deserve special attention in line with WHO priorities [37].

The age-standardised YLD estimates generated by the GBD 2019 study show slight variation over time and across geographic areas and are subject to large levels of uncertainty. The former is mainly driven by the fact that the GBD severity distributions do not vary over time and space [38], essentially reducing differences in YLD rates to differences in the underlying prevalence estimates. Since prevalence data are typically sparser and more uncertain than mortality data, the modelled prevalence estimates further tend to smooth out temporal and spatial heterogeneity. In parallel, EU countries would need to improve the quality and performance of their health information systems, strengthening and integrating data available through disease registers, claims data, primary care data, hospital discharge data and health surveys.

This study is important and timely as it reflects the state of health in the EU prior to a number of major changes, including the COVID-19 pandemic and Brexit (the departure of the UK from the EU), and therefore will likely be important for policy-makers to understand the state of health of Europe at this pivotal moment in time. Although the UK is not included in the analysis and that potential adverse effects of Brexit on the health of the UK have been discussed [39], less is known about how it could impact the remaining EU-27. To date, there has been wide variation in the resilience and responses of health systems and governments to the pandemic across the EU, which replicates many of the regional variations presented in this study of the state of health of the EU. Comparing the results of this study with post-pandemic and post-Brexit GBD data will therefore be crucial to assess the impact of these ‘shocks’ on the health of EU citizens. Moreover, it could be pivotal for policy makers to address in future studies. Another strength of this study is that it provides estimates at the national level for EU countries for which burden of disease studies are lacking or are scarce and can support priority setting and resource allocations. This study used estimates provided by the GBD 2019 study and hence shares some limitations with other GBD studies, predominantly related mostly to the availability and quality of primary data, in particular for morbidity, which might not be homogeneous across EU countries. Moreover, there are some limitations pertaining to this paper related to: (1) the study design as it is a descriptive study, does not aim to estimate the effect of EU level policies; (2) timeline (as it provides an overall EU-level assessment across 10 years and excludes in-depth national assessment taking into account the year of accession to the EU); and (3) data availability. In addition, GBD metrics apply the same disability weights for all countries and regions. Such limitations have been widely discussed in the literature [15, 38].

Regarding the age-standardisation, it is also essential to highlight that while it is essential to ensure a global and comparable age standardisation, the used world standard population by GBD instead of a European standard population may change the ranking of causes [40].

In conclusion, although population health in the EU has been improving, large differences between countries persist. Health outcomes remain much better in Western or Southern Europe (e.g. Spain, Italy or France) than in Central and Eastern Europe (e.g. Bulgaria or Romania) or the Baltic states (e.g. Latvia or Lithuania). NCDs, particularly neoplasms and cardiovascular diseases continue to be the leading causes of disease burden. This study suggests that addressing the prevalence and incidence of diseases and injuries should be a priority for EU health policy makers, emphasising reducing health inequalities across the block. Attention must be paid to specific causes, including mental disorders, given their impact on YLD [41]. This study highlights that there are many opportunities for mutual learning among otherwise similar EU countries with different patterns of disease and injury.

The datasets analysed during the current study are publicly available in the GBD 2019 Results Tool and GBD 2019 Compare repositories (https://vizhub.healthdata.org/gbd-results/ and https://vizhub.healthdata.org/gbd-compare, respectively).

The authors would like to acknowledge the networking support from COST Action CA18218 (European Burden of Disease Network), supported by COST (European Cooperation in Science and Technology). This article was supported by National Funds through FCT - Fundação para a Ciência e a Tecnologia,I.P., within CINTESIS, R&D Unit (reference UIDB/4255/2020).

GBD 2019 EU State of Health Collaborators

João Vasco Santos, MD, 1,2 Alicia Padron-Monedero, PhD, 3 Boris Bikbov, MD, 4 Diana Alecsandra Grad, BA, 5,6 Dietrich Plass, DrPH, 7 Enkeleint A Mechili, PhD, 8,9 Federica Gazzelloni, BSc, 10 Florian Fischer, PhD, 11 Gerhard Sulo, PhD, 12 Che Henry Ngwa, MSc, 13 Prof Isabel Noguer-Zambrano, PhD, 3 Prof José L Peñalvo, PhD, 14,15 Juanita A Haagsma, PhD, 16 Katarzyna Kissimova-Skarbek, PhD, 17 Lorenzo Monasta, DSc, 18 Nermin Ghith, PhD, 19 Prof Rodrigo Sarmiento-Suárez, MPH, 20,3 Rok Hrzic, MSc, 21 Romana Haneef, PhD, 22 Rónán O'Caoimh, PhD, 23,24 Sarah Cuschieri, PhD, 25 Prof Stefania Mondello, NA, 26 Zubair Kabir, PhD, 27 Cristiana Abbafati, PhD, 28 Hassan Abolhassani, PhD, 29,30 Victor Adekanmbi, PhD, 31 Keivan Ahmadi, PhD, 32 Sepideh Ahmadi, PhD, 33 Prof Adel Al-Jumaily, PhD, 34,35 Prof François Alla, PhD, 36 Jordi Alonso, MD, 37,38 Prof Robert Ancuceanu, PhD, 39 Catalina Liliana Andrei, PhD, 40 Prof Tudorel Andrei, PhD, 41 Sofia Androudi, PhD, 42 Prof Josep M Antó, MD, 43,44 Seth Christopher Yaw Appiah, PhD, 45,46 Olatunde Aremu, PhD, 47 Benedetta Armocida, MSc, 48 Prof Johan Ärnlöv, PhD, 49,50 Ashokan Arumugam, PhD, 51,52 Sameh Attia, MSc, 53 Avinash Aujayeb, MBBS, 54 Prof Marcel Ausloos, PhD, 55,41 Prof Jose L Ayuso-Mateos, PhD, 56,57 Prof Maciej Banach, PhD, 58,59 Prof Till Winfried Bärnighausen, MD, 60,61 Francesco Barone-Adesi, PhD, 62 Sandra Barteit, PhD, 63 Sanjay Basu, PhD, 64,32 Prof Bernhard T Baune, PhD, 65,66 Massimiliano Beghi, MD, 67 Luis Belo, PhD, 68,69 Derrick A Bennett, PhD, 70 Prof Antonio Biondi, PhD, 71 Mahdi Bohluli, PhD, 72,73 Israel Júnior Borges do Nascimento, MD, 74,75 Nicola Luigi Bragazzi, PhD, 76 Tasanee Braithwaite, PhD, 77,78 Prof Hermann Brenner, MD, 79 Danilo Buonsenso, MD, 80,81 Prof Reinhard Busse, PhD, 82 Prof Daniela Calina, PhD, 83 Giulia Carreras, PhD, 84 Márcia Carvalho, PhD, 85,69 Giulio Castelpietra, PhD, 86,87 Prof Alberico L Catapano, PhD, 88,89 Maria Sofia Cattaruzza, PhD, 90 Joht Singh Chandan, MFPH, 91 Periklis Charalampous, MSc, 16 Vijay Kumar Chattu, MD, 92,93 Simiao Chen, DSc, 60 Prof Rajiv Chowdhury, PhD, 94,95 Prof Hanne Christensen, DMSci, 96 Sheng-Chia Chung, PhD, 97,98 Joao Conde, PhD, 99 Barbara Corso, PhD, 100 Prof Natália Cruz-Martins, PhD, 101,102 Giovanni Damiani, MD, 103,104 Alejandro de la Torre-Luque, PhD, 105 Andreas K Demetriades, MD, 106,107 Nikolaos Dervenis, MD, 108,109 Mostafa Dianatinasab, MSc, 110,111 Prof Diana Dias da Silva, PhD, 112,69 Abdel Douiri, PhD, 113 Prof David Edvardsson, PhD, 114,115 Luchuo Engelbert Bain, PhD, 116 Francesco Esposito, MD, 117 Adeniyi Francis Fagbamigbe, PhD, 118,119 Carla Sofia e Sá Farinha, MSc, 120,121 Seyed-Mohammad Fereshtehnejad, PhD, 49,122 João C Fernandes, PhD, 123 Pietro Ferrara, MD, 124 Peter Andras Gaal, PhD, 125,126 Silvano Gallus, DSc, 127 Lucia Galluzzo, MA, 48 Mariana Gaspar Fonseca, PhD, 128 Prof Gus Gazzard, MD, 129,130 Alessandro Gialluisi, PhD, 131 Simona Giampaoli, MD, 132 Prof Paramjit Singh Gill, DM, 133 James C Glasbey, MSc, 134 Giuseppe Gorini, MD, 135 Prof Michal Grivna, PhD, 136,137 Abdul Hafiz, PhD, 138,139 Josep Maria Haro, MD, 140,141 Prof Jan Hartvigsen, PhD, 142,143 Prof Simon I Hay, FMedSci, 144,145 Behzad Heibati, PhD, 146 David Hillus, MD, 147 Mehdi Hosseinzadeh, PhD, 148,149 Mihaela Hostiuc, PhD, 150 Sorin Hostiuc, PhD, 151,152 Salman Hussain, PhD, 153,154 Prof Gaetano Isola, PhD, 155 Olatunji Johnson, PhD, 156 Prof Jost B Jonas, MD, 157,158 Tamas Joo, PhD, 125,159 Jacek Jerzy Jozwiak, PhD, 160 Mikk Jürisson, PhD, 161 Marina Karanikolos, PhD, 162,163 Joonas H Kauppila, MD, 164,165 Moien AB Khan, MSc, 166,167 Khaled Khatab, PhD, 168,169 Miloslav Klugar, PhD, 153,170 Ai Koyanagi, MD, 171,172 Om P Kurmi, PhD, 173,174 Dian Kusuma, DSc, 175,176 Prof Carlo La Vecchia, MD, 177 Ben Lacey, PhD, 70,178 Demetris Lamnisos, PhD, 179 Prof Heidi Jane Larson, PhD, 180,144 Prof Anders O Larsson, PhD, 181,182 Savita Lasrado, MS, 183 Paolo Lauriola, MD, 184 Prof Jeffrey V Lazarus, PhD, 185 Caterina Ledda, PhD, 186 Paul H Lee, PhD, 187 Mall Leinsalu, PhD, 188,189 Matilde Leonardi, MD, 190 Miriam Levi, PhD, 191,192 An Li, PhD, 193,194 Christine Linehan, PhD, 195 Prof Giancarlo Logroscino, PhD, 196,197 Prof Stefan Lorkowski, PhD, 198,199 Joana A Loureiro, PhD, 200,201 Prof Ronan A Lyons, MD, 202 Áurea M Madureira-Carvalho, PhD, 112,203 Prof Azeem Majeed, MD, 204 Alexander G Mathioudakis, PhD, 205,206 Colm McAlinden, PhD, 207 Prof John J McGrath, MD, 208,209 Prof Ritesh G Menezes, MD, 210 Alexios-Fotios A Mentis, MD, 211 Atte Meretoja, MD, 212,213 Tuomo J Meretoja, MD, 214,215 Tomislav Mestrovic, PhD, 216,144 Junmei Miao Jonasson, PhD, 217 Bartosz Miazgowski, MD, 218,219 Prof Tomasz Miazgowski, MD, 220 Andreea Mirica, PhD, 41 Shafiu Mohammed, PhD, 221,82 Ali H Mokdad, PhD, 144,145 Prof Ute Mons, PhD, 222 Joana Morgado-da-Costa, MSc, 223 Francesk Mulita, PhD, 224,225 Prof Christopher J L Murray, DPhil, 144,145 Ionut Negoi, PhD, 226,227 Ruxandra Irina Negoi, PhD, 228,229 Serban Mircea Negru, MD, 230 Evangelia Nena, MD, 231 Nurulamin M Noor, MRCP, 232,233 George Ntaios, PhD, 234 Prof Bogdan Oancea, PhD, 235 Frank B Osei, PhD, 236,237 Adrian Otoiu, PhD, 41 Raffaele Palladino, MD, 238,204 Songhomitra Panda-Jonas, MD, 239 Prof Shahina Pardhan, PhD, 240 Jay Patel, NA, 241,242 Prof Mihaela Paun, PhD, 243,244 Paolo Pedersini, MSc, 245 Umberto Pensato, MD, 246 Renato B Pereira, PhD, 247 Prof Jorge Pérez-Gómez, PhD, 248 Norberto Perico, MD, 249 Ionela-Roxana Petcu, PhD, 41 Carrie B Peterson, PhD, 250 Marina Pinheiro, PhD, 247 Prof Maarten J Postma, PhD, 251,252 Alberto Raggi, PhD, 190 Amir Masoud Rahmani, PhD, 253 Chythra R Rao, MD, 254 Prof Salman Rawaf, MD, 204,255 Reza Rawassizadeh, PhD, 256 Prof Giuseppe Remuzzi, MD, 249 Abanoub Riad, DDS, 257,153 Prof Simona Sacco, MD, 258 Prof Mohammad Reza Saeb, PhD, 259 Brijesh Sathian, PhD, 260,261 Davide Sattin, PsyD, 262 Prof Nikolaos Scarmeas, PhD, 263,264 Prof Falk Schwendicke, PhD, 265 Rahman Shiri, PhD, 266 Velizar Shivarov, PhD, 267,268 Kibrom T Sibhatu, PhD, 269 Prof Biagio Simonetti, PhD, 270,271 Prof Søren T Skou, PhD, 142,272 Prof Joan B Soriano, MD, 273,274 Ireneous N Soyiri, PhD, 275 Prof Nicholas Steel, PhD, 276,277 Simona Cătălina Ștefan, PhD, 278 Fridolin Steinbeis, MD, 147 Paschalis Steiropoulos, MD, 231 Leo Stockfelt, PhD, 279 Prof Saverio Stranges, MD, 280,281 Prof Johan Sundström, PhD, 181,282 Prof Rafael Tabarés-Seisdedos, PhD, 283,284 Arulmani Thiyagarajan, MPH, 285 Roman Topor-Madry, PhD, 286,287 Marcos Roberto Tovani-Palone, PhD, 288,289 Nikolaos Tsilimparis, PhD, 290 Brigid Unim, PhD, 48 Marco Vacante, PhD, 71 Jef Van den Eynde, BSc, 291 Prof Tommi Juhani Vasankari, MD, 292,293 Prof Massimiliano Veroux, PhD, 294 Jorge Hugo Villafañe, PhD, 245 Prof Francesco S Violante, MD, 295,296 Yanzhong Wang, PhD, 113 Ronny Westerman, DSc, 297 Prof Charles D A Wolfe, MD, 113,298 Grant M A Wyper, MSc, 299 Prof Sanni Yaya, PhD, 300,301 Prof Vesna Zadnik, PhD, 302 Jean-David Zeitoun, PhD, 303,304 Prof Alimuddin Zumla, PhD, 305,306 Alberto Freitas, PhD, 307,1 Prof. Brecht Devleesschauwer, PhD. 308,309

Affiliations

1 CINTESIS@RISE, MEDCIDS, Faculty of Medicine, University of Porto, Porto, Portugal; 2 Public Health Unit, ULS Santo António, Porto, Portugal; 3 National School of Public Health, Institute of Health Carlos III, Madrid, Spain; 4 Scientific-Tools.Org, Bergamo, Italy; 5 Research Department, RoNeuro Institute for Neurological Research and Diagnostic, Cluj-Napoca, Romania; 6 Department of Public Health, Babes-Bolyai University, Cluj-Napoca, Romania; 7 Department for Exposure Assessment and Environmental Health Indicators, German Environment Agency, Dessau-Roßlau, Germany; 8 Department of Healthcare, University of Vlora, Vlora, Albania; 9 Clinic of Social and Family Medicine, University of Crete, Heraklion, Greece; 10 Independent researcher; 11 Institute of Gerontological Health Services and Nursing Research, Ravensburg-Weingarten University of Applied Sciences, Weingarten, Germany; 12 Department of Disease Burden, Norwegian Institute of Public Health, Bergen, Norway; 13 Department of Epidemiology and Population Health, Faculty of Health Sciences, American University of Beirut, Beirut, Lebanon; 14 National Center for Epidemiology, Instituto de Salud Carlos III, Madrid, Spain; 15 The Gerald J. and Dorothy R. Friedman School of Nutrition Science and Policy, Tufts University, Boston, MA, USA; 16 Department of Public Health, Erasmus University Medical Center, Rotterdam, Netherlands; 17 Department of Health Economics and Social Security, Jagiellonian University Medical College, Krakow, Poland; 18 Clinical Epidemiology and Public Health Research Unit, Burlo Garofolo Institute for Maternal and Child Health, Trieste, Italy; 19 Research group for Childhood Cancer, Danish Cancer Institute, Danish Cancer Society, Copenhagen, Denmark; 20 Department of Health and Society, Faculty of Medicine, University of Applied and Environmental Sciences, Bogota, Colombia; 21 Department of International Health, Maastricht University, Maastricht, Netherlands; 22 Department of Non-communicable Diseases and Injuries, Santé Publique France (Public Health France), Saint-Maurice, France; 23 Department of Medicine, University College Cork, Cork, Ireland; 24 Department of Geriatric Medicine, Mercy University Hospital, Cork, Ireland; 25 Anatomy Department, University of Malta, Msida, Malta; 26 Department of Biomedical and Dental Sciences and Morphofunctional Imaging, Messina University, Messina, Italy; 27 School of Public Health, University College Cork, Cork, Ireland; 28 Department of Juridical and Economic Studies, La Sapienza University, Rome, Italy; 29 Research Center for Immunodeficiencies, Tehran University of Medical Sciences, Tehran, Iran; 30 Department of Biosciences and Nutrition, Karolinska University Hospital, Huddinge, Sweden; 31 Department of Obstetrics & Gynecology, University of Texas, Galveston, TX, USA; 32 School of Public Health, Imperial College London, London, UK; 33 School of Advanced Technologies in Medicine, Shahid Beheshti University of Medical Sciences, Tehran, Iran; 34 School of Computing, Mathematics and Engineering, Charles Sturt University, Wagga Wagga, NSW, Australia; 35 Information and Communication Sciences and Technologies Pole, Mathematics, Algorithms and Decision Team, ENSTA Bretagne, Brest, France; 36 Bordeaux School of Public Health, University of Bordeaux, Bordeaux, France; 37 Research Program of Epidemiology and Public Health, Pompeu Fabra University, Barcelona, Spain; 38 Department of Experimental and Health Sciences, Biomedical Research Networking Center in Epidemiology and Public Health (CiberESP), Madrid, Spain; 39 Faculty of Pharmacy, Carol Davila University of Medicine and Pharmacy, Bucharest, Romania; 40 Cardiology Department, Carol Davila University of Medicine and Pharmacy, Bucharest, Romania; 41 Department of Statistics and Econometrics, Bucharest University of Economic Studies, Bucharest, Romania; 42 Department of Medicine, University of Thessaly, Volos, Greece; 43 Non-Communicable Diseases & Environment Programme, Barcelona Institute for Global Health, Barcelona, Spain; 44 Department of Experimental and Health Sciences, Pompeu Fabra University, Barcelona, Spain; 45 Department of Sociology and Social Work, Kwame Nkrumah University of Science and Technology, Kumasi, Ghana; 46 Center for International Health, Ludwig Maximilians University, Munich, Germany; 47 Department of Public Health, Birmingham City University, Birmingham, UK; 48 Department of Cardiovascular, Endocrine-metabolic Diseases and Aging, National Institute of Health, Rome, Italy; 49 Department of Neurobiology, Care Sciences and Society, Karolinska Institute, Stockholm, Sweden; 50 School of Health and Social Studies, Dalarna University, Falun, Sweden; 51 Department of Physiotherapy, University of Sharjah, Sharjah, United Arab Emirates; 52 Department Community Medicine and Rehabilitation, Umeå University, Umea, Sweden; 53 Oral and Maxillofacial Surgery, Justus Liebig University of Giessen, Giessen, Germany; 54 Northumbria HealthCare NHS Foundation Trust, National Health Service (NHS) Scotland, Newcastle upon Tyne, UK; 55 School of Business, University of Leicester, Leicester, UK; 56 Department of Psychiatry, Autonomous University of Madrid (Universidad Autónoma de Madrid), Madrid, Spain; 57 CIBERSAM, Institute of Health Carlos III, Madrid, Spain; 58 Department of Hypertension, Medical University of Lodz, Lodz, Poland; 59 Polish Mothers' Memorial Hospital Research Institute, Lodz, Poland; 60 Heidelberg Institute of Global Health (HIGH), Heidelberg University, Heidelberg, Germany; 61 T.H. Chan School of Public Health, Harvard University, Boston, MA, USA; 62 Department of Translational Medicine, University of Eastern Piedmont, Novara, Italy; 63 Heidelberg Institute of Global Health (HIGH), Heidelberg University Hospital, Heidelberg, Germany; 64 Center for Primary Care, Harvard University, Boston, MA, USA; 65 Department of Psychiatry, University of Münster, Münster, Germany; 66 Department of Psychiatry, Melbourne Medical School, Melbourne, VIC, Australia; 67 Department of Mental Health, AUSL Romagna, Ravenna, Italy; 68 Biological Sciences Department, University of Porto, Porto, Portugal; 69 Research Unit on Applied Molecular Biosciences (UCIBIO), University of Porto, Porto, Portugal; 70 Nuffield Department of Population Health, University of Oxford, Oxford, UK; 71 Department of General Surgery and Medical-Surgical Specialties, University of Catania, Catania, Italy; 72 Department of Computer Science and Information Technology, Institute for Advanced Studies in Basic Sciences, Zanjan, Iran; 73 Department of Research and Innovation, Petanux Research GmBH, Bonn, Germany; 74 School of Medicine and University Hospital, Federal University of Minas Gerais, Belo Horizonte, Brazil; 75 Division of Country Health Policies and Systems, World Health Organization (WHO), Denmark, Denmark; 76 University of Genoa, Genoa, Italy; 77 Ophthalmology Department, Moorfields Eye Hospital NHS Foundation Trust, London, UK; 78 International Centre for Eye Health, London School of Hygiene & Tropical Medicine, London, UK; 79 Division of Clinical Epidemiology and Aging Research, German Cancer Research Center, Heidelberg, Germany; 80 Department of Woman and Child Health and Public Health, Agostino Gemelli University Polyclinic IRCCS (Fondazione Policlinico Universitario A. Gemelli IRCCS), Roma, Italy; 81 Global Health Research Institute, Università Cattolica del Sacro Cuore (Catholic University of Sacred Heart), Roma, Italy; 82 Department of Health Care Management, Technical University of Berlin, Berlin, Germany; 83 Clinical Pharmacy, University of Medicine and Pharmacy of Craiova, Romania, Craiova, Romania; 84 Institute for Cancer Research, Prevention and Clinical Network, Florence, Italy; 85 Faculty of Health Sciences, University Fernando Pessoa, Porto, Portugal; 86 Department of Medicine, University of Udine, Udine, Italy; 87 Department of Mental Health, Healthcare Agency "Friuli Occidentale", Pordenone, Italy; 88 Department of Pharmacological and Biomolecular Sciences, University of Milan, Milan, Italy; 89 MultiMedica, IRCCS, Sesto S. Giovanni, Italy; 90 Department of Public Health and Infectious Diseases, La Sapienza University, Rome, Italy; 91 Institute of Applied Health Research, University of Birmingham, Birmingham, UK; 92 Faculty of Medical Sciences, University of the West Indies, St Augustine, Trinidad and Tobago; 93 Independent Consultant, Athens, Greece; 94 Florida International University, Florida International University, Miami, FL, USA; 95 Department of Epidemiology, University of Bern, Bern, Switzerland; 96 Bispebjerg Hospital, University of Copenhagen, Copenhagen, Denmark; 97 Department of Health Informatics, University College London, London, UK; 98 Health Data Research UK, London, UK; 99 Nova Medical School, Nova University of Lisbon, Lisbon, Portugal; 100 Institute of Neuroscience, National Research Council, Pisa, Italy; 101 Therapeutic and Diagnostic Technologies, Cooperativa de Ensino Superior Politécnico e Universitário (Polytechnic and University Higher Education Cooperative), Gandra, Portugal; 102 Institute for Research and Innovation in Health, University of Porto, Porto, Portugal; 103 IRCCS Istituto Ortopedico Galeazzi (Galeazzi Orthopedic Institute IRCCS), University of Milan, Milan, Italy; 104 Department of Dermatology, Case Western Reserve University, Cleveland, OH, USA; 105 Department of Legal Medicine, Psychiatry and Pathology, Complutense University of Madrid (Universidad Complutense de Madrid), Madrid, Spain; 106 Department of Neurosurgery, University of Edinburgh, Edinburgh, UK; 107 Department of Neurosurgery, National Health Service (NHS) Scotland, Edinburgh, UK; 108 St Paul's Eye Unit, Royal Liverpool University Hospital, Liverpool, UK; 109 Department of Ophthalmology, Aristotle University of Thessaloniki, Thessaloniki, Greece; 110 Department of Epidemiology, Maastricht University, Maastricht, Netherlands; 111 Department of Epidemiology, Shiraz University of Medical Sciences, Shiraz, Iran; 112 Toxicology Research Unit (TOXRUN), Cooperativa de Ensino Superior Politécnico e Universitário (CESPU) (University Polytechnic Higher Education Cooperative), Gandra, Portugal; 113 School of Population Health and Environmental Sciences, King's College London, London, UK; 114 School of Nursing and Midwifery, La Trobe University, Melbourne, VIC, Australia; 115 Department of Nursing, Umeå University, Umea, Sweden; 116 Lincoln International Institute for Rural Health, University of Lincoln, Lincoln, UK; 117 Dipartimento di Scienze Biomediche e Neuromotorie (Department of Biomedical and Neuromotor Sciences), University of Bologna, Bologna, Italy; 118 Department of Epidemiology and Medical Statistics, University of Ibadan, Ibadan, Nigeria; 119 Institute of Applied Health Sciences, University of Aberdeen, Aberdeen, UK; 120 Dissemination Division, National Institute of Statistics, Lisbon, Portugal; 121 Activity Planning and Control Unit, Directorate-General of Health (DGS), Lisbon, Portugal; 122 Division of Neurology, University of Ottawa, Ottawa, ON, Canada; 123 Center for Biotechnology and Fine Chemistry, Catholic University of Portugal, Porto, Portugal; 124 Research Center on Public Health, University of Milan Bicocca, Monza, Italy; 125 Health Services Management Training Centre, Semmelweis University, Budapest, Hungary; 126 Department of Applied Social Sciences, Sapientia Hungarian University of Transylvania, Târgu-Mureş, Romania; 127 Department of Environmental Health Sciences, Mario Negri Institute for Pharmacological Research, Milan, Italy; 128 National Health Service, London, UK; 129 Institute of Ophthalmology, University College London, London, UK; 130 Moorfields Eye Hospital NHS Foundation Trust, London, UK; 131 Department of Epidemiology and Prevention, IRCCS Neuromed, Pozzilli, Italy; 132 Department of Cardiovascular Endocrine-metabolic Diseases and Aging, Istituto Superiore di Sanità, Rome, Italy; 133 Warwick Medical School, University of Warwick, Coventry, UK; 134 NIHR Global Health Research Unit on Global Surgery, University of Birmingham, Birmingham, UK; 135 Oncological Network, Prevention and Research Institute, Institute for Cancer Research, Prevention and Clinical Network, Florence, Italy; 136 College of Medicine and Health Sciences, United Arab Emirates University, Al Ain, United Arab Emirates; 137 Department of Public Health and Preventive Medicine, Charles University, Prague, Czech Republic; 138 College of Medicine, Umm AL Qura University, Makkah, Saudi Arabia; 139 MSc Epidemiology Programme, London School of Hygiene & Tropical Medicine, London, UK; 140 Research Unit, University of Barcelona, Barcelona, Spain; 141 Biomedical Research Networking Center for Mental Health Network (CiberSAM), Barcelona, Spain; 142 Department of Sports Science and Clinical Biomechanics, University of Southern Denmark, Odense, Denmark; 143 Research Department, Nordic Institute of Chiropractic and Clinical Biomechanics, Odense, Denmark; 144 Institute for Health Metrics and Evaluation, University of Washington, Seattle, WA, USA; 145 Department of Health Metrics Sciences, School of Medicine, University of Washington, Seattle, WA, USA; 146 Research Unit of Population Health, University of Oulu, Oulu, Finland; 147 Department of Infectious Diseases and Respiratory Medicine, Charité Medical University Berlin, Berlin, Germany; 148 Institute of Research and Development, Duy Tan University, Da Nang, Viet Nam; 149 Department of Computer Science, University of Human Development, Sulaymaniyah, Iraq; 150 Internal Medicine Department, Carol Davila University of Medicine and Pharmacy, Bucharest, Romania; 151 Department of Legal Medicine and Bioethics, Carol Davila University of Medicine and Pharmacy, Bucharest, Romania; 152 Clinical Legal Medicine Department, National Institute of Legal Medicine Mina Minovici, Bucharest, Romania; 153 Czech National Centre for Evidence-based Healthcare and Knowledge Translation, Masaryk University, Brno, Czech Republic; 154 Institute of Biostatistics and Analyses, Masaryk University, Brno, Czech Republic; 155 Department of General Surgery and Surgical-Medical Specialties, University of Catania, Catania, Italy; 156 Department of Mathematics, University of Manchester, Manchester, UK; 157 Institute of Molecular and Clinical Ophthalmology Basel, Basel, Switzerland; 158 Department of Ophthalmology, Heidelberg University, Mannheim, Germany; 159 Hungarian Health Management Association, Budapest, Hungary; 160 Department of Family Medicine and Public Health, University of Opole, Opole, Poland; 161 Institute of Family Medicine and Public Health, University of Tartu, Tartu, Estonia; 162 European Observatory on Health Systems and Policies, London School of Hygiene & Tropical Medicine, London, UK; 163 Department of Health Services Research and Policy, London School of Hygiene & Tropical Medicine, London, UK; 164 Surgery Research Unit, University of Oulu, Oulu, Finland; 165 Department of Molecular Medicine and Surgery, Karolinska Institute, Stockholm, Sweden; 166 Family Medicine Department, United Arab Emirates University, Al Ain, United Arab Emirates; 167 Primary Care Department, NHS North West London, London, UK; 168 Faculty of Health and Wellbeing, Sheffield Hallam University, Sheffield, UK; 169 College of Arts and Sciences, Ohio University, Zanesville, OH, USA; 170 Institute for Health Information and Statistics of the Czech Republic, Prague, Czech Republic; 171 Biomedical Research Networking Center for Mental Health Network (CIBERSAM), San Juan de Dios Sanitary Park, Sant Boi de Llobregat, Spain; 172 Catalan Institution for Research and Advanced Studies (ICREA), Barcelona, Spain; 173 Faculty of Health and Life Sciences, Coventry University, Coventry, UK; 174 Department of Medicine, McMaster University, Hamilton, ON, Canada; 175 Department of Health Services Research and Management, City University of London, London, UK; 176 Faculty of Public Health, University of Indonesia, Depok, Indonesia; 177 Department of Clinical Sciences and Community Health, University of Milan, Milan, Italy; 178 National Institute for Health Research (NIHR) Oxford Biomedical Research Centre, Oxford, UK; 179 Department of Health Sciences, European University Cyprus, Nicosia, Cyprus; 180 Department of Infectious Disease Epidemiology, London School of Hygiene & Tropical Medicine, London, UK; 181 Department of Medical Sciences, Uppsala University, Uppsala, Sweden; 182 Department of Clinical Chemistry and Pharmacology, Uppsala University Hospital, Uppsala, Sweden; 183 Department of Otorhinolaryngology, Father Muller Medical College, Mangalore, India; 184 International Society Doctors for the Environment, Arezzo, Italy; 185 Barcelona Institute for Global Health, Barcelona, Spain; 186 Clinical and Experimental Medicine, University of Catania, Catania, Italy; 187 Department of Health Sciences, University of Leicester, Leicester, UK; 188 School of Social Sciences, Södertörn University, Huddinge, Sweden; 189 Department of Epidemiology and Biostatistics, National Institute for Health Development, Tallinn, Estonia; 190 UO Neurologia, Salute Pubblica e Disabilità, Fondazione IRCCS Istituto Neurologico Carlo Besta (Neurology, Public Health and Disability Unit, Carlo Besta Neurological Institute), Milan, Italy; 191 Department of Prevention, USL Tuscany Center, Firenze, Italy; 192 Department of Health Sciences, University of Florence, Florence, Italy; 193 Center for Dentistry and Oral Hygiene, University of Groningen, Groningen, Netherlands; 194 Stomatological Hospital, Southern Medical University, Guangzhou, China; 195 UCD Centre for Disability Studies, University College Dublin, Dublin, Ireland; 196 Department of Basic Medical Sciences, Neuroscience and Sense Organs, University of Bari Aldo Moro, Bari, Italy; 197 Department of Clinical Research in Neurology, Fondazione Cardinale Giovanni Panico Hospital, Tricase, Italy; 198 Institute of Nutritional Sciences, Friedrich Schiller University Jena, Jena, Germany; 199 Competence Cluster for Nutrition and Cardiovascular Health (nutriCARD), Jena, Germany; 200 Laboratory for Process Engineering, Environment, Biotechnology and Energy (LEPABE), University of Porto, Porto, Portugal; 201 School of Health, Polytechnic Institute of Porto, Portugal; 202 School of Medicine, Swansea University, Swansea, UK; 203 Laboratório de Farmacognosia (LAQV) (Associated Laboratory for Green Chemistry, University of Porto, Porto, Portugal; 204 Department of Primary Care and Public Health, Imperial College London, London, UK; 205 Division of Infection, Immunity and Respiratory Medicine, University of Manchester, Manchester, UK; 206 North West Lung Centre, Manchester University NHS Foundation Trust, Manchester, UK; 207 Department of Ophthalmology, Singleton Hospital, Swansea, UK; 208 Queensland Brain Institute, The University of Queensland, Brisbane, QLD, Australia; 209 National Centre for Register-based Research, Aarhus University, Aarhus, Denmark; 210 Forensic Medicine Division, Imam Abdulrahman Bin Faisal University, Dammam, Saudi Arabia; 211 International Dx Department, BGI Genomics, Copenhagen, Denmark; 212 Neurology Unit, Helsinki University Hospital, Helsinki, Finland; 213 School of Health Sciences, University of Melbourne, Melbourne, VIC, Australia; 214 Breast Surgery Unit, Helsinki University Hospital, Helsinki, Finland; 215 University of Helsinki, Helsinki, Finland; 216 University Centre Varazdin, University North, Varazdin, Croatia; 217 School of Public Health and Community Medicine, University of Gothenburg, Gothenburg, Sweden; 218 Center for Innovation in Medical Education, Pomeranian Medical University, Szczecin, Poland; 219 Pomeranian Medical University, Szczecin, Poland; 220 Department of Propedeutics of Internal Diseases & Arterial Hypertension, Pomeranian Medical University, Szczecin, Poland; 221 Health Systems and Policy Research Unit, Ahmadu Bello University, Zaria, Nigeria; 222 Faculty of Medicine and University Hospital Cologne, University of Cologne, Cologne, Germany; 223 University Hospital Center of Porto, University of Porto, Porto, Portugal; 224 Department of Surgery, General University Hospital of Patras, Patras, Greece; 225 Medical School, University of Thessaly, Larissa, Greece; 226 Department of General Surgery, Carol Davila University of Medicine and Pharmacy, Bucharest, Romania; 227 Department of General Surgery, Emergency Hospital of Bucharest, Bucharest, Romania; 228 Department of Anatomy and Embryology, Carol Davila University of Medicine and Pharmacy, Bucharest, Romania; 229 Department of Cardiology, Cardio-Aid, Bucharest, Romania; 230 Department of Oncology, Victor Babes University of Medicine and Pharmacy, Timisoara, Romania; 231 Department of Medicine, Democritus University of Thrace, Alexandroupolis, Greece; 232 Medical Research Council Clinical Trials Unit, University College London, London, UK; 233 Department of Gastroenterology, Cambridge University Hospitals, Cambridge, UK; 234 Department of Internal Medicine, University of Thessaly, Larissa, Greece; 235 Department of Applied Economics and Quantitative Analysis, University of Bucharest, Bucharest, Romania; 236 Faculty of Geo-Information Science and Earth Observation, University of Twente, Enschede, Netherlands; 237 Department of Mathematics and Statistics, University of Energy and Natural Resources, Sunyani, Ghana; 238 Department of Public Health, University of Naples Federico II, Naples, Italy; 239 Privatpraxis, Heidelberg, Germany; 240 Vision and Eye Research Institute, Anglia Ruskin University, Cambridge, UK; 241 Global Health Governance Programme, University of Edinburgh, Edinburgh, UK; 242 School of Dentistry, University of Leeds, Leeds, UK; 243 Department of Bioinformatics and Biostatistics, National Institute of Research and Development for Biological Sciences, Bucharest, Romania; 244 Department of Statistics and Cybernetics, University of Bucharest, Bucharest, Romania; 245 Clinical Research Department, IRCCS Fondazione Don Carlo Gnocchi, Milan, Italy; 246 Department of Neurology, IRCCS Humanitas Research Hospital, Milan, Italy; 247 Department of Chemistry, University of Porto, Porto, Portugal; 248 Departamento de Didáctica de la Expresión Musical, Plástica y Corportal, University of Extremadura, Cáceres, Spain; 249 Mario Negri Institute for Pharmacological Research, Bergamo, Italy; 250 Independent Consultant, Copenhagen, Denmark; 251 University Medical Center Groningen, University of Groningen, Groningen, Netherlands; 252 Center of Excellence in Higher Education for Pharmaceutical Care Innovation, Universitas Padjadjaran (Padjadjaran University), Bandung, Indonesia; 253 Future Technology Research Center, National Yunlin University of Science and Technology, Yunlin, Taiwan; 254 Department of Community Medicine, Manipal Academy of Higher Education, Manipal, India; 255 Academic Public Health England, Public Health England, London, UK; 256 Department of Computer Science, Boston University, Boston, MA, USA; 257 Department of Public Health, Masaryk University, Brno, Czech Republic; 258 Department of Neurology, University of L'Aquila, L'Aquila, Italy; 259 Department of Polymer Technology, Independent Consultant, Gdansk, Poland; 260 Geriatric and Long Term Care Department, Hamad Medical Corporation, Doha, Qatar; 261 Faculty of Health & Social Sciences, Bournemouth University, Bournemouth, UK; 262 IRCCS Istituti Clinici Scientifici Maugeri (IRCCS Maugeri Scientific Clinical Institute), Milan, Italy; 263 Department of Neurology, National and Kapodistrian University of Athens, Athens, Greece; 264 Department of Neurology, Columbia University, New York, NY, USA; 265 Oral Diagnosis, Digital Health and Health Services Research, Charité University Medical Center Berlin, Berlin, Germany; 266 Finnish Institute of Occupational Health, Helsinki, Finland; 267 Clinical Immunology and Hematology, Sofiamed University Hospital, Sofia, Bulgaria; 268 Department of Genetics, Sofia University "St. Kliment Ohridiski", Sofia, Bulgaria; 269 Department of Agricultural Economics and Rural Development, University of Göttingen, Göttingen, Germany; 270 Department of Law, Economics, Management and Quantitative Methods, University of Sannio, Benevento, Italy; 271 WSB University in Gdańsk, Gdańsk, Poland; 272 Department of Physiotherapy and Occupational Therapy, Næstved-Slagelse-Ringsted Hospitals, Slagelse, Denmark; 273 Hospital Universitario de La Princesa (Princess University Hospital), Autonomous University of Madrid, Madrid, Spain; 274 Centro de Investigación Biomédica en Red Enfermedades Respiratorias (CIBERES) (Center for Biomedical Research in Respiratory Diseases Network), Madrid, Spain; 275 Hull York Medical School, University of Hull, Hull City, UK; 276 Department of Primary Care and Public Health, University of East Anglia, Norwich, UK; 277 Public Health England, London, UK; 278 Management Department, Bucharest University of Economic Studies, Bucharest, Romania; 279 Occupational and Environmental Medicine Department, University of Gothenburg, Gothenburg, Sweden; 280 Department of Epidemiology & Biostatistics, The University of Western Ontario, London, ON, Canada; 281 Department of Population Health, Luxembourg Institute of Health, Strassen, Luxembourg; 282 The George Institute for Global Health, Sydney, NSW, Australia; 283 Department of Medicine, University of Valencia, Valencia, Spain; 284 Institute of Health Carlos III, Biomedical Research Networking Center for Mental Health Network (CiberSAM), Madrid, Spain; 285 Clinical Epidemiology, Leibniz Institute for Prevention Research and Epidemiology, Bremen, Germany; 286 Institute of Public Health, Jagiellonian University Medical College, Kraków, Poland; 287 Agency for Health Technology Assessment and Tariff System, Warsaw, Poland; 288 Saveetha Dental College and Hospitals, Saveetha Institute of Medical and Technical Sciences (SIMATS), Chennai, India; 289 Modestum LTD, Eastbourne, UK; 290 Department of Vascular Surgery, Ludwig Maximilians University, Munich, Germany; 291 Department of Cardiovascular Sciences, Katholieke Universiteit Leuven, Leuven, Belgium; 292 UKK Institute, Tampere, Finland; 293 Faculty of Medicine and Health Technology, Tampere University, Tampere, Finland; 294 Department of Medical and Surgical Sciences and Advanced Technologies, University of Catania, Catania, Italy; 295 Department of Medical and Surgical Sciences, University of Bologna, Bologna, Italy; 296 Occupational Health Unit, Sant'Orsola Malpighi Hospital, Bologna, Italy; 297 Competence Center of Mortality-Follow-Up of the German National Cohort, Federal Institute for Population Research, Wiesbaden, Germany; 298 NIHR-Biomedical Research Centre (NIHR-BRC), Guy's and St. Thomas' Hospital and Kings College London, London, UK; 299 School of Health and Wellbeing, University of Glasgow, Glasgow, UK; 300 School of International Development and Global Studies, University of Ottawa, Ottawa, ON, Canada; 301 The George Institute for Global Health, Imperial College London, London, UK; 302 Epidemiology and Cancer Registry Sector, Institute of Oncology Ljubljana, Ljubljana, Slovenia; 303 Centre of Clinical Epidemiology, Hôtel Dieu Hospital, Assistance Publique Hôpitaux de Paris (Public Hospitals of Paris), Paris, France; 304 Gastroenterology and Nutrition, Saint-Antoine Hospital, Assistance Publique Hôpitaux de Paris (Public Hospitals of Paris), Paris, France; 305 Department of Infection, University College London, London, UK; 306 NIHR-Biomedical Research Centre (NIHR-BRC), University College London Hospitals, London, UK; 307 Department of Community Medicine, Information and Health Decision Sciences, University of Porto, Porto, Portugal; 308 Department of Epidemiology and Public Health, Sciensano, Brussels, Belgium; 309 Department of Translational Physiology, Infectiology and Public Health, Ghent University, Ghent, Belgium.

Only secondary data was used for this study.

T W Bärnighausen was supported by the Alexander von Humboldt Foundation through the Alexander von Humboldt Professor award, funded by the German Federal Ministry of Education and Research. L Belo acknowledges the support from FCT in the scope of the project UIDP/04378/2020 and UIDB/04378/2020 of UCIBIO and the project LA/P/0140/2020 of i4HB. D A Bennett is supported by the UK Medical Research Council Population Health Research Unit at the University of Oxford. M Carvalho acknowledges the support from FCT in the scope of the project UIDP/04378/2020 and UIDB/04378/2020 of UCIBIO and the project LA/P/0140/2020 of i4HB. A L Catapano is supported in part by the Ministero della Salute ricerca corrente. J S Chandan acknowledges the National Institute of Health Research. J Conde would like to acknowledge the European Research Council Starting Grant (ERC-StG-2019–848325). D Dias da Silva acknowledges the projects UIDP/04378/2022 and UIDB/04378/2022 of the Research Unit on Applied Molecular Biosciences UCIBIO; the project LA/P/ 0140/2022 of the Associate Laboratory Institute for Health and Bioeconomy i4HB; and IINFACTS-Institute of Research and Advanced Training in Health Sciences and Technologies (project PsiloPharm) and TOXRUN Toxicology Research Unit, University Institute of Health Sciences, IUCS-CESPU, Portugal. A Douiri acknowledges support by King’s Health Partners/Guy’s and St Thomas Charity “MLTC Challenge Fund” (grant number EIC180702) and the NIHR Applied Research Collaboration (ARC) South London at King’s College Hospital NHS Foundation Trust. The views expressed are those of the authors and not necessarily those of the NIHR or the Department of Health and Social Care. J C Fernandes acknowledges support from Fundação para a Ciência e Tecnologia (FCT) with funding for UID/Multi/50016/2019. G Gazzard acknowledges support from NIHR Biomedical Research Centre at Moorfields Eye Hospital NHS Foundation Trust, London, UK and Institute of Ophthalmology, University College London, UK. P S Gill acknowledges being NIHR senior investigator for the NIHR Department of Health and Social Care. The views expressed are those of the author(s) and not necessarily those of the NHS, the NIHR or the Department of Health and Social Care. J C Glasbey is supported by a UK National Institute of Health Research Doctoral Research Fellowship (NIHR300175). S Hussain was supported from Operational Programme Research, Development and Education “Project, Postdoc2MUNI” (No.CZ.02.2.69/0.0/0.0/18_053/0016952). M AB Khan acknowledges support as recipient of research grants G00003634- CMHS “NP-22–20 80, 000 AED (2021), G00003569 NP-21–13 80,000 AED, and 1976—SDG Research Program Grant 40,000 AED. B Lacey acknowledges support from UK Biobank, which is funded largely by the UK Medical Research Council and Wellcome. J A Loureiro was supported by National Funds through Fundação para a Ciência e Tecnologia (FCT) under the Scientific Employment Stimulus’ Institutional Call—[CEECINST/00049/2018]. S Lorkowski acknowledges institutional support from the Competence Cluster for Nutrition and Cardiovascular Health (nutriCARD) Halle-Jena-Leipzig (Germany; German Federal Ministry of Education and Research; grant agreement number 01EA1808A). A G Mathioudakis acknowledges support by the National Institute for Health and Care Research Manchester Biomedical Research Centre (NIHR Manchester BRC) and by an NIHR Clinical Lectureship in Respiratory Medicine. J J McGrath was supported by the Danish National Research Foundation (Niels Bohr Professorship) and is employed by The Queensland Centre for Mental Health Research, which receives core funding from the Queensland Health. S Mohammed reports fellowship grant from Alexander von Humboldt Foundation, outside the submitted work. L Monasta received support from the Italian Ministry of Health, through the contribution given to the Institute for Maternal and Child Health IRCCS Burlo Garofolo, Trieste, Italy (RC 34/2017). P Pedersini was supported and funded by the Italian Ministry of Health—Ricerca Corrente 2021. M Pinheiro thanks FCT for funding through program DL 57/2016 Norma transita. A Raggi acknowledges support by the Italian Ministry of Health (RRC). A Riad was supported by the project of the Ministry of Education, Youth and Sports of the Czech Republic (Systemic Risk Institute "SYRI": LX22NPO5101) and the projects of Masaryk University (MUNI/A/1402/2021 and MUNI/IGA/1104/2021). S T Skou is currently funded by a grant from Region Zealand (Exercise First) and two grants from the European Union’s Horizon 2020 Research and Innovation Program, one from the European Research Council (MOBILIZE, grant agreement No 801790) and the other under grant agreement No 945377 (ESCAPE). J B Soriano is supported by Centro de Investigacion Biomedica en Red de Enfermedades Respiratorias, Instituto de Salud Carlos III, Madrid, Spain. L Stockfelt was funded by the Swedish state under the agreement between the Swedish government and the country councils, the ALF-agreement. Johan Sundström acknowledges stock ownership in Anagram kommunikation AB and Symptoms Europe AB. R Tabares-Seisdedos is supported by the Spanish Ministry of Science and Innovation, Institute of Health Carlos III, CIBERSAM, INCLIVA (PID2021-129099OB-I00). M R Tovani-Palone acknowledges Saveetha Institute of Medical and Technical Sciences (SIMATS) for its support. J H Villafañe was supported and funded by the Italian Ministry of Health—Ricerca Corrente 2021. A Zumla acknowledges grant support from the Pan-African Network for Rapid Research, Response, Relief and Preparedness for Infectious Diseases Epidemics (PANDORA-ID-NET) ONE-HEALTH (Europe-Africa) consortium funded by the European and Developing Countries Clinical Trials Partnership, which is supported by Horizon 2020, the EU's Framework Programme for Research and Innovation.